Conversation Pieces

The first time I went to a foreign country as a grown-up, a great calm came over me. Before, I had traveled almost always in America, where I feel it is my obligation to eavesdrop on my fellow citizens whenever I can. I don't go out of my way to snoop, but any conversation or other word spoken within my hearing in the normal course of events I believe I must eavesdrop on and pay close attention to, in case they hold a clue - to what? I'm not sure, exactly, but it's important, whatever it is. Constant eavesdropping is a demanding chore. When I was first in a country where I didn't speak the language and couldn't eavesdrop even if I wanted to, I felt a sudden sense of happy relief, as if school had been called off for the day.

The nosiness of eavesdropping is punished by how boring it is, often. A lot of what you overhear is not very interesting. Once you start, though, it's hard to stop. You're following conversations, despite yourself, and there's nothing you can do. During countless hours I've groaned inwardly at the tedium of what I was overhearing, hoping for some loud industrial noise or police action to blot it out and rescue me. Usually the only way out is to suffer through. At a Christmas program at my son's school I find myself in front of two moms with camcorders. The program is so rigorously non-religious, such a miscellany of generic holiday-ness, that the only tension keeping the audience involved is waiting for one's own kid to come on. On the long stretches in between, the moms behind me talk, and I listen helplessly to every word. Where their camcorders were purchased and how much they cost and what they do, and the problems encountered in looking for various video games in various stores, and when the next shipment of a prized video game is expected at which store, and - you get the idea.

I used to eavesdrop a lot during bus rides. In my twenties I rode the Greyhound for thousands of miles around the country, and it seemed to me that I heard people in buses say anything and everything. Maybe you remember that Allman Brothers song, "Ramblin' Man," where the guy says that he was born in the backseat of the Greyhound bus rollin' down highway 41. Well, I'm not positive, but I think I was sitting just a few seats away when that occurred. It sounded like it, anyway. In the twilight tinted bus windows, to the background noise of empty soda cans rolling around on the floor, I listened in on one crazed, sad, discursive, endless personal drama after another. Once I heard a woman catalogue the sins of a man sitting next to her, enumerating his many infidelities and lies and cheapnesses and betrayals. I could not fathom why the woman had continued to put up with such mistreatment; when the bus got into the station I finally glanced at the offender, and recognized him as a semi-famous former rock star. Sometimes people I listened to got wackier and louder and louder and wackier until they drove the whole bus nuts and the driver had to stop and call the highway patrol.

Some people I overheard are more prominent in my memory than acquaintances I've known for years. One guy in particular stays with me - a Vietnam vet who I sat just behind on a long nighttime bus ride in the South. This guy would not shut up. He talked about fast cars, big black snakes, guns, ammo, rock 'n' roll, marijuana, women, hunting dogs. Late at night when most people on the bus were asleep he began to talk about a person he had killed in Vietnam, and how he hadn't wanted to kill her, and how bad he felt about the killing. Everything he said was kind of a question, a wondering what his hearer made of it. The man sitting beside him listened, murmuring, noncommittal, kind. I am ashamed now to think of how unsympathetic in my heart I was to the guy, as I silently condemned him for intruding on the general peace with his frantic monologue. At the Miami bus station, at the end of the ride, I took a good look at him for the first time. He was short, knobby, skinny, with a hollow chest. His light brown hair, soft as in a shampoo ad, hung to his shoulders, and his eyes were large, hound-like, and watery. He caught my look, and no doubt saw the irritation - the witless, ignorant, irritation - in my eyes. He looked back at me without anger, straightforwardly, beseechingly.

A few conversations I've overheard were so dreamy and absorbing that I hated for them to end. Once on an Amtrak train from Chicago to southern Illinois I heard two older black ladies behind me talking about produce from their gardens, and canning. Their talk was a spoken song about peaches and tomatoes and damson plums and pickled beets, and different types and sizes of canning jars, and how the jars and lids and seals should be prepared, and how many cans of this or that fruit or vegetable each of them had "put up." Regularly, for chorus, they would agree with each other; one lady would make a remark, and the other would agree, and then the first would agree with her agreement. Meanwhile in the train’s window the city and its suburbs fell behind, replaced by cornfields and backyard clotheslines and small towns with water towers.

I keep lists of remarks I’ve overheard: “He’s got a good job - he just sits behind a desk and issues tools”; and “I would never eat a banana that way. Never”; and “he brought his leg with him!” (other person: “Oh, no!”); and “Jane, I made a sincere effort…”; and “I mean, when you’re so nervous you cant breathe, and your breath is your instrument…”; and “Jimmy, listen to me - welfare is not an exact science”; and “The idea of ‘fun’ Italian food makes me ill”; and “I don’t think that’s the catheter that’s going to set the world on fire”; and “Oh, no, I only wear solid colors”; and “No, no no! Tippi Hedren”; and “He travels more than you used to work” (other voice: “What do you mean by that crack?” First voice: “it’s not a ‘crack’, it’s a statement”). Sometimes a conversation will pique me so much that I want to butt in and demand new details, as I almost did recently on a flight from Seattle to Anchorage, Alaska, when the man behind me began talking about the problems of a friend of his whose hearing aid attracted bats.

The remark about the catheter that wouldn’t set the world on fire was made by one medical equipment salesman to another in a crowded hospital waiting room. The two salesman had opened their sample cases and were comparing their wares, passing time in congenial shop talk. Meanwhile all around them where waiting patients and their families sunk in various medical discomforts and miseries. When I heard him say that, I briefly emerged from my own depths. Here was a new entry for my collections of overhears! “I don’t think that’s the catheter that’s going to set the world on fire”: I repeated it over and over to myself, so I could copy it down as soon as I got home. I wanted to shake the guy’s hand, thank him, congratulate him. He kept on talking, unaware of the remarkable sentence he’d just uttered. Like an analgesic, his remark provided sweet abstraction between the mind and pain.

Of course, that’s partly what I’m hoping for in my obsessive listening-in. Sometimes I hear a remark that’s so pretty or funny or bizarre that it lifts me from the ordinariness of the day. Often I get additional thrill from the realization, as happened in the waiting room, that I’m the only one who knows what a marvel had just occurred. In daily life most of us are like dogs, listening bot to the meaning but to the sound. Sometimes when I overhear a conversation I realize that besides me, no one, including the speakers themselves, is listening to what they say.

If you make your living as a journalist, as I have done, you learn that almost nobody listens to anybody else; a reason why people tell journalists such scandalous personal details is that nobody closer will pay them any mind. That’s why, also, I’ve always found the term “investigative journalism” a strange one. We don’t notice what’s right in front of us, to begin with; why should journalism need some new, extra-tenacious, deep-digging kind of observation in order to be serious and real? As it happens, I believe in the opposite kind of journalism, the non-investigate kind. I believe in the truth of what can be seen on the surface by anyone. Listen to a person long and attentively enough, and he’ll let you know the truth, even if his intent is to deceive. And maybe if you listen to people in general - to the myriad unguarded bits and pieces of conversation flying around among the passers-by - you’ll get a Whitmanesque sense of America that’s simple and democratic and grand.

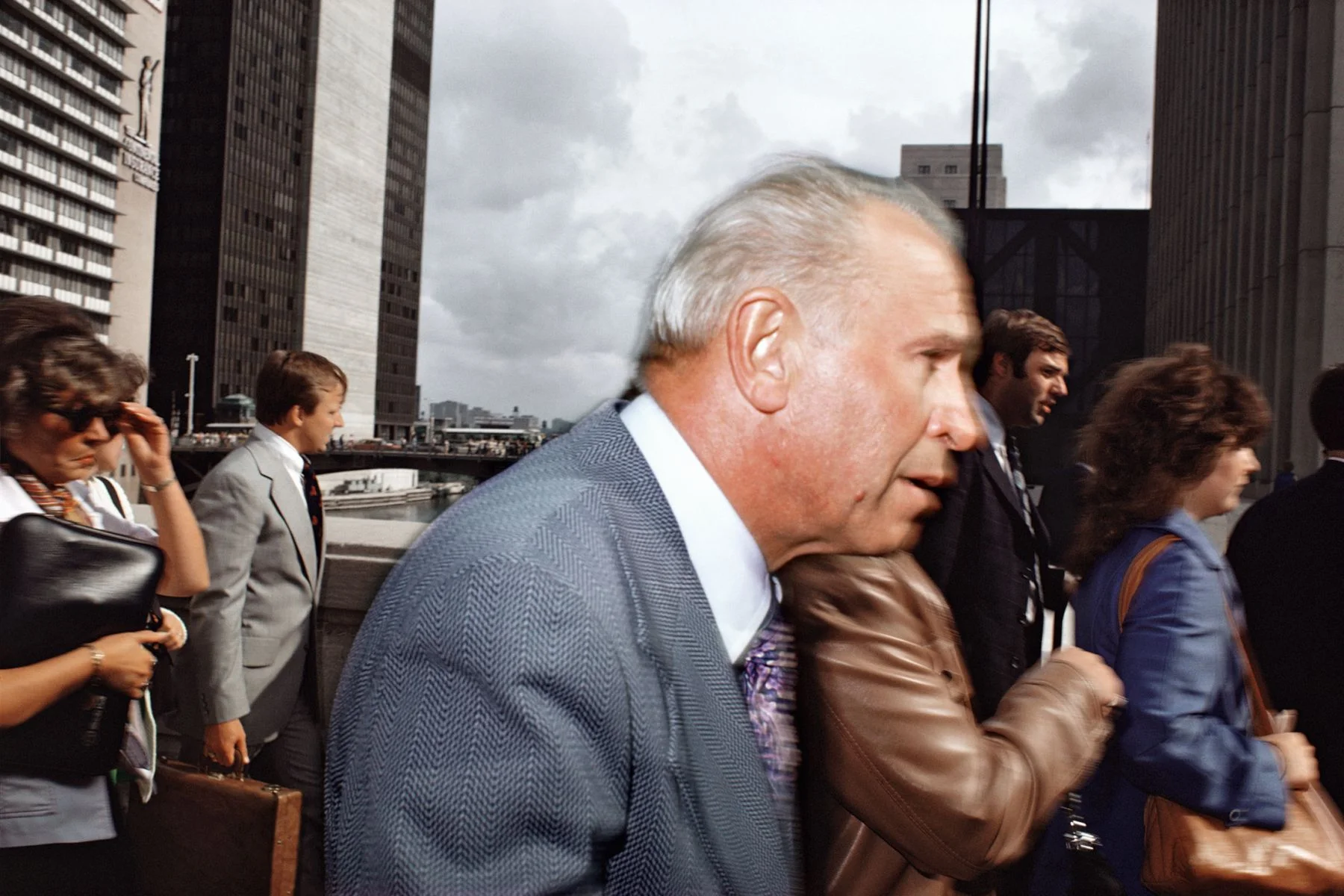

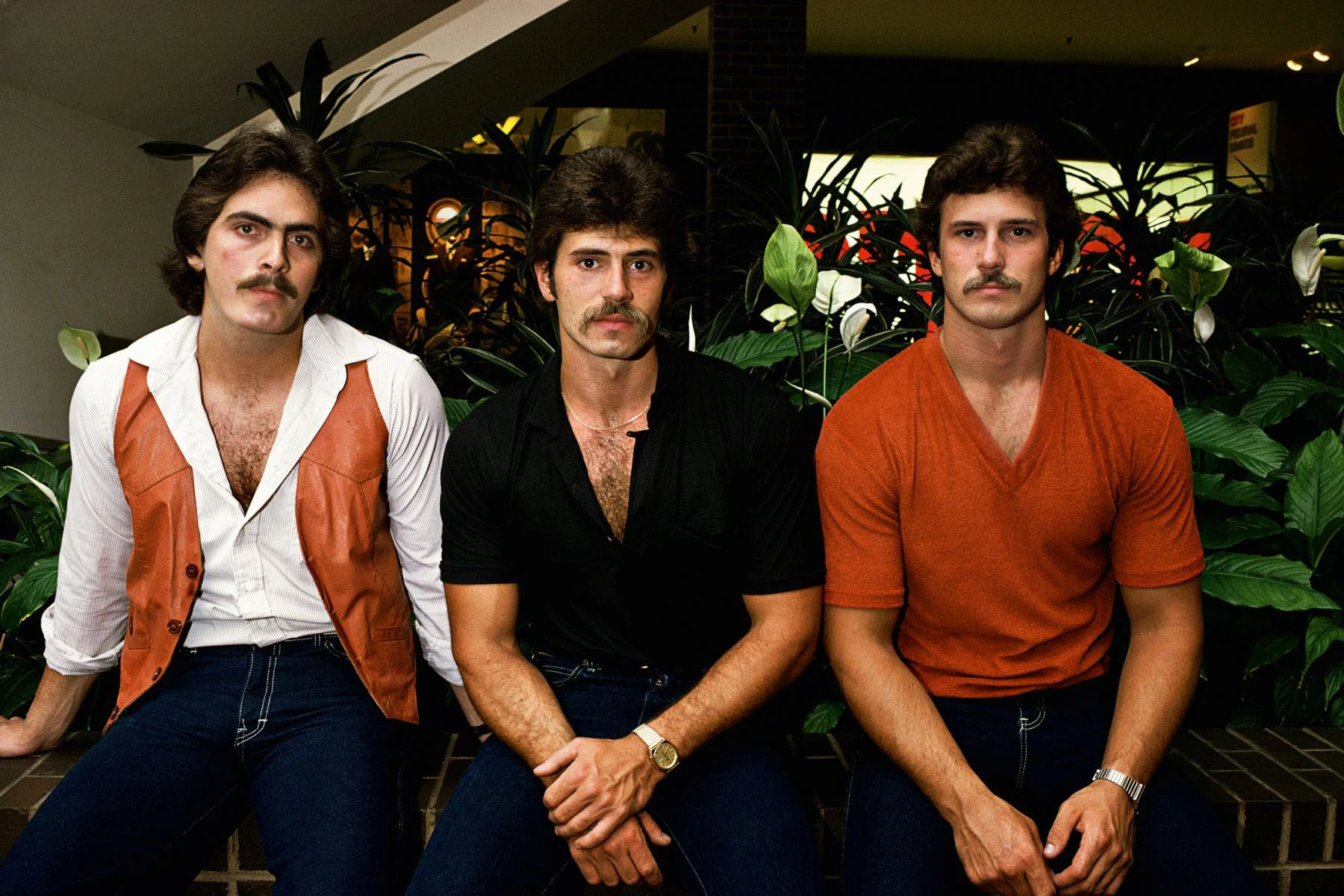

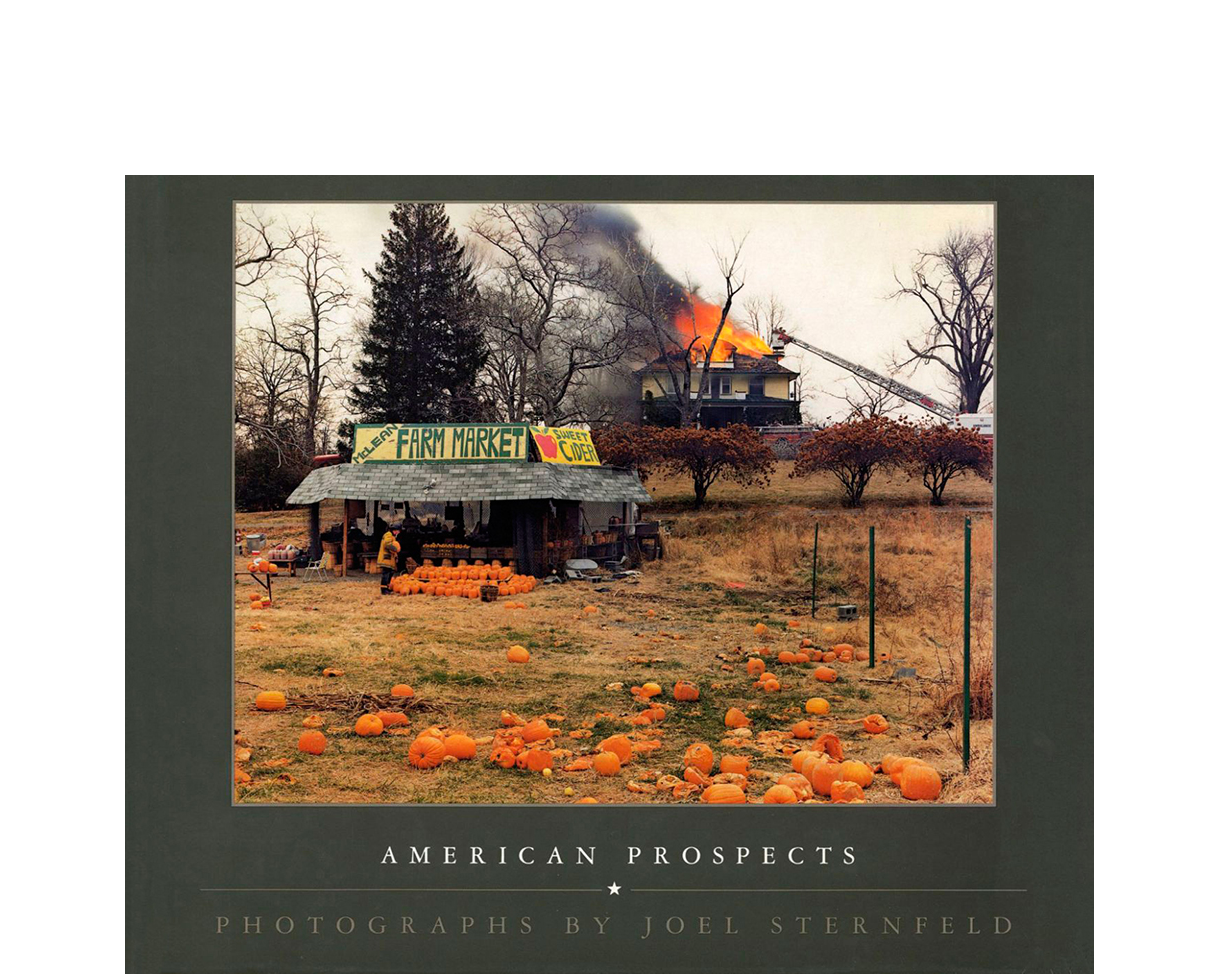

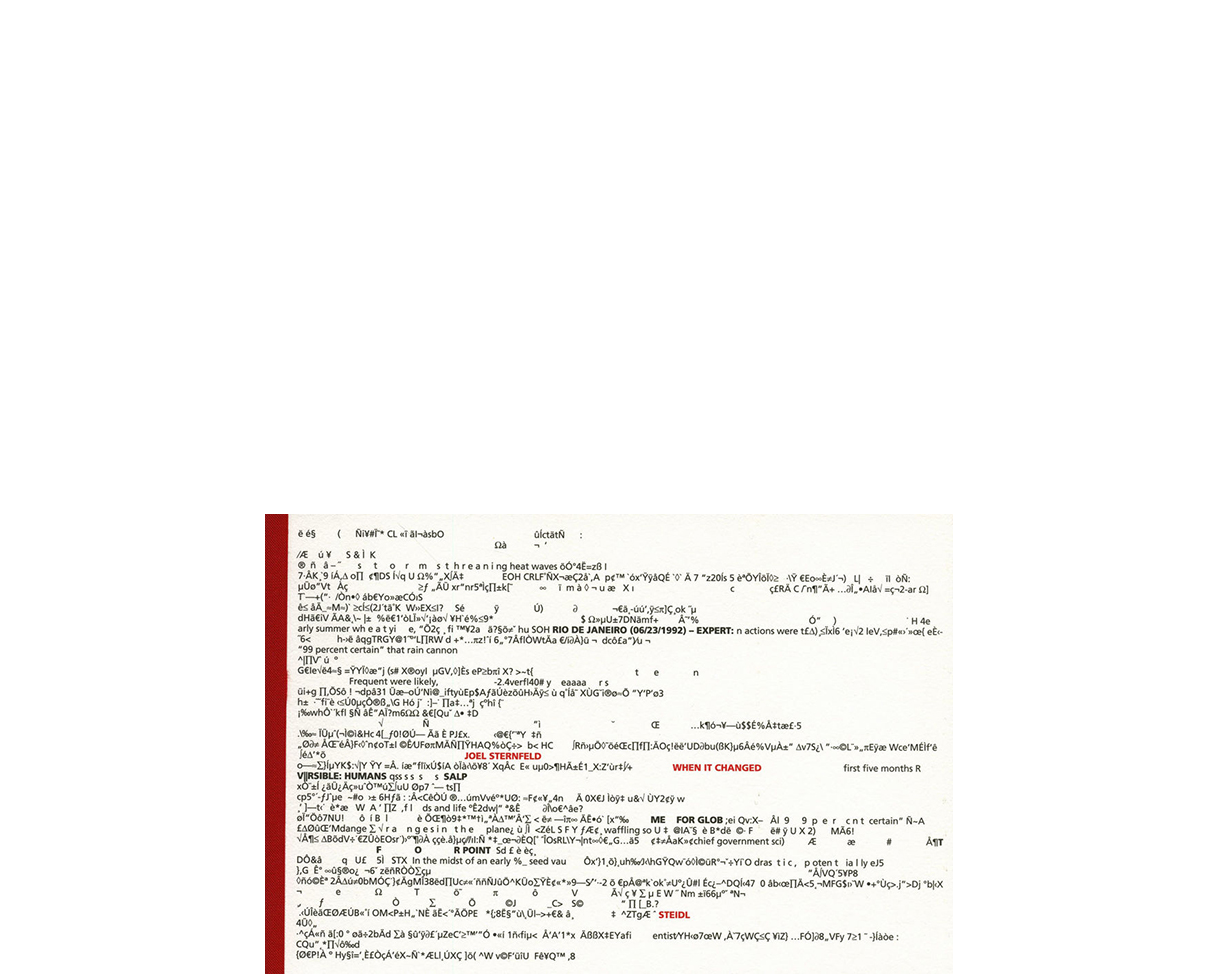

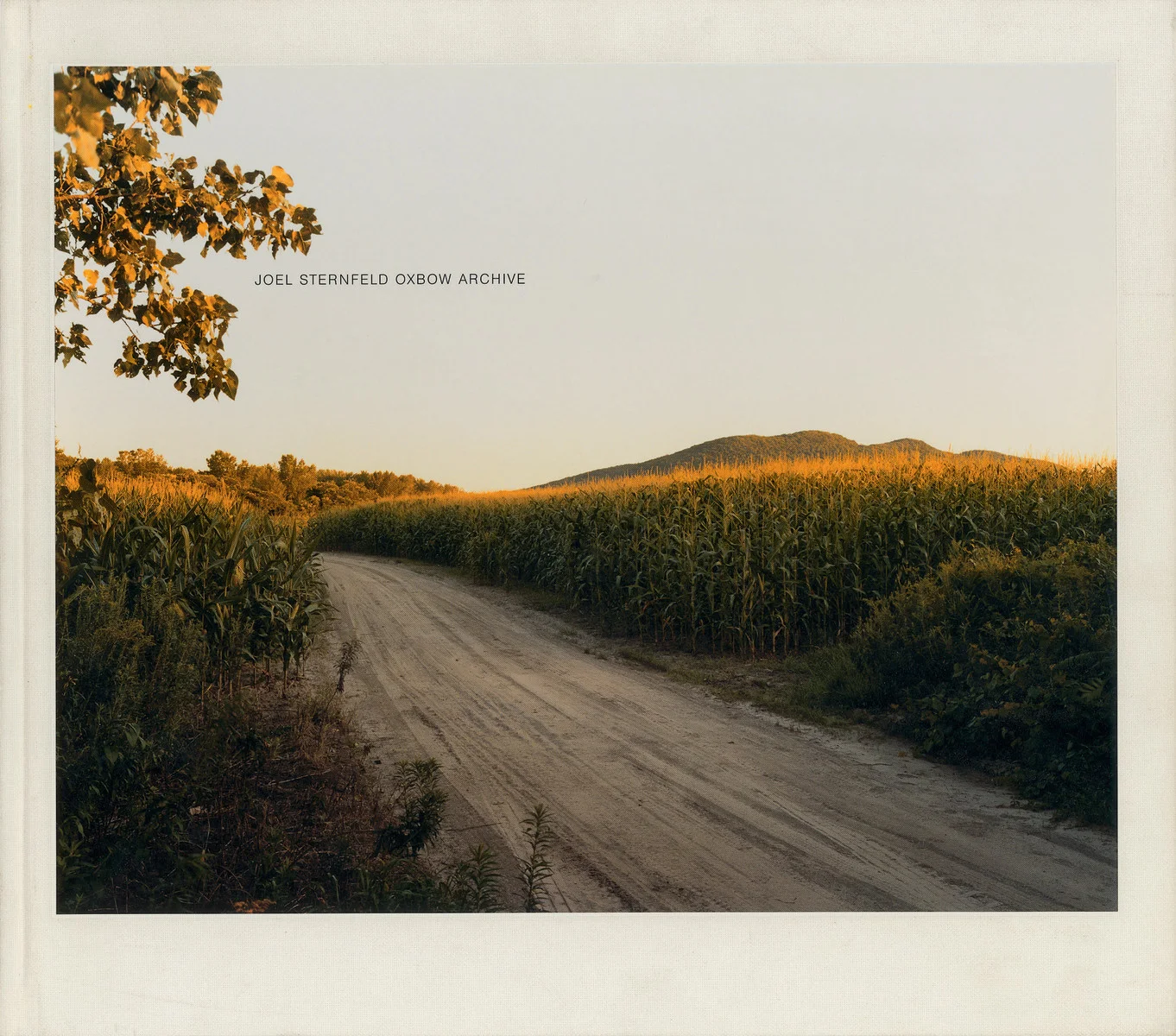

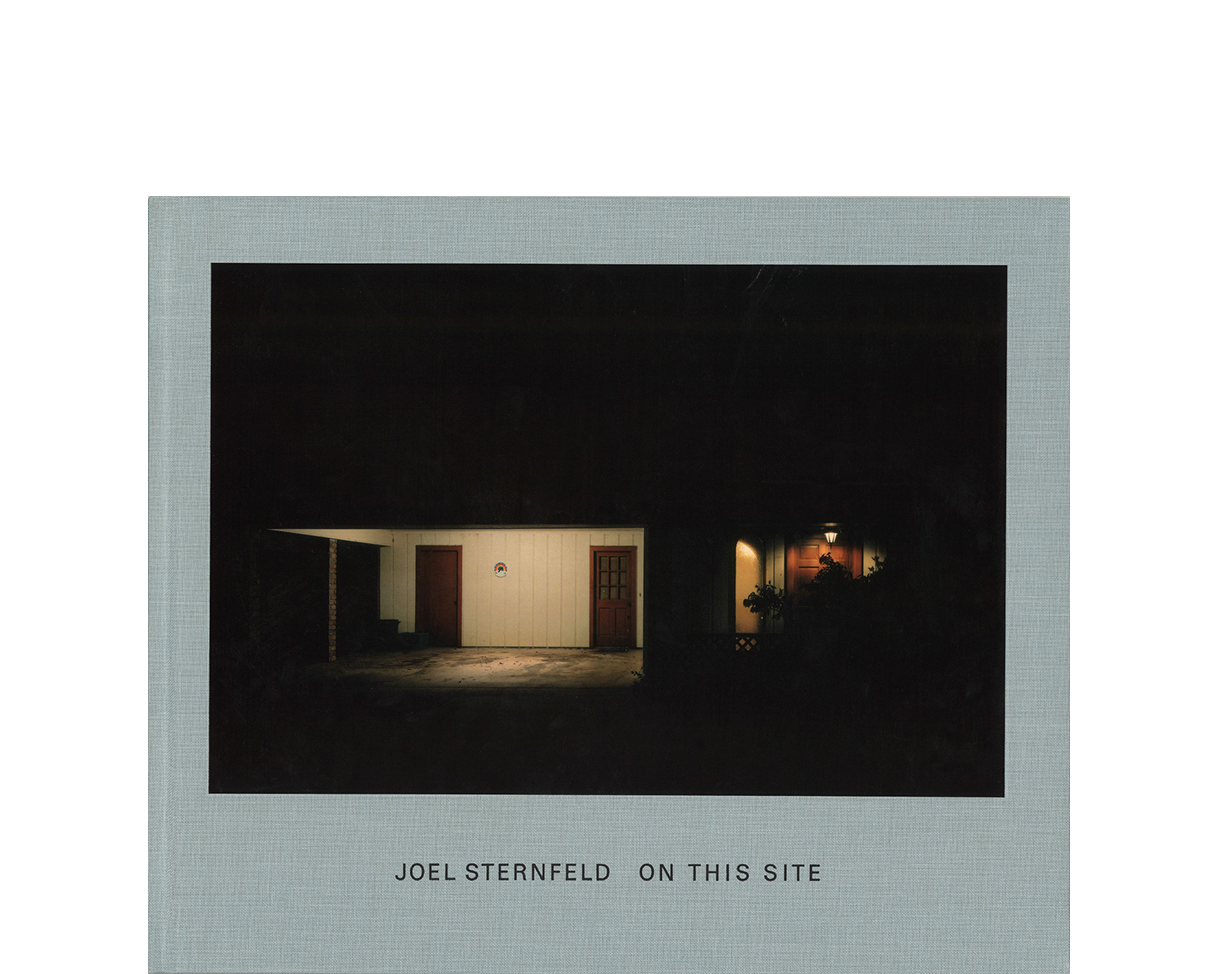

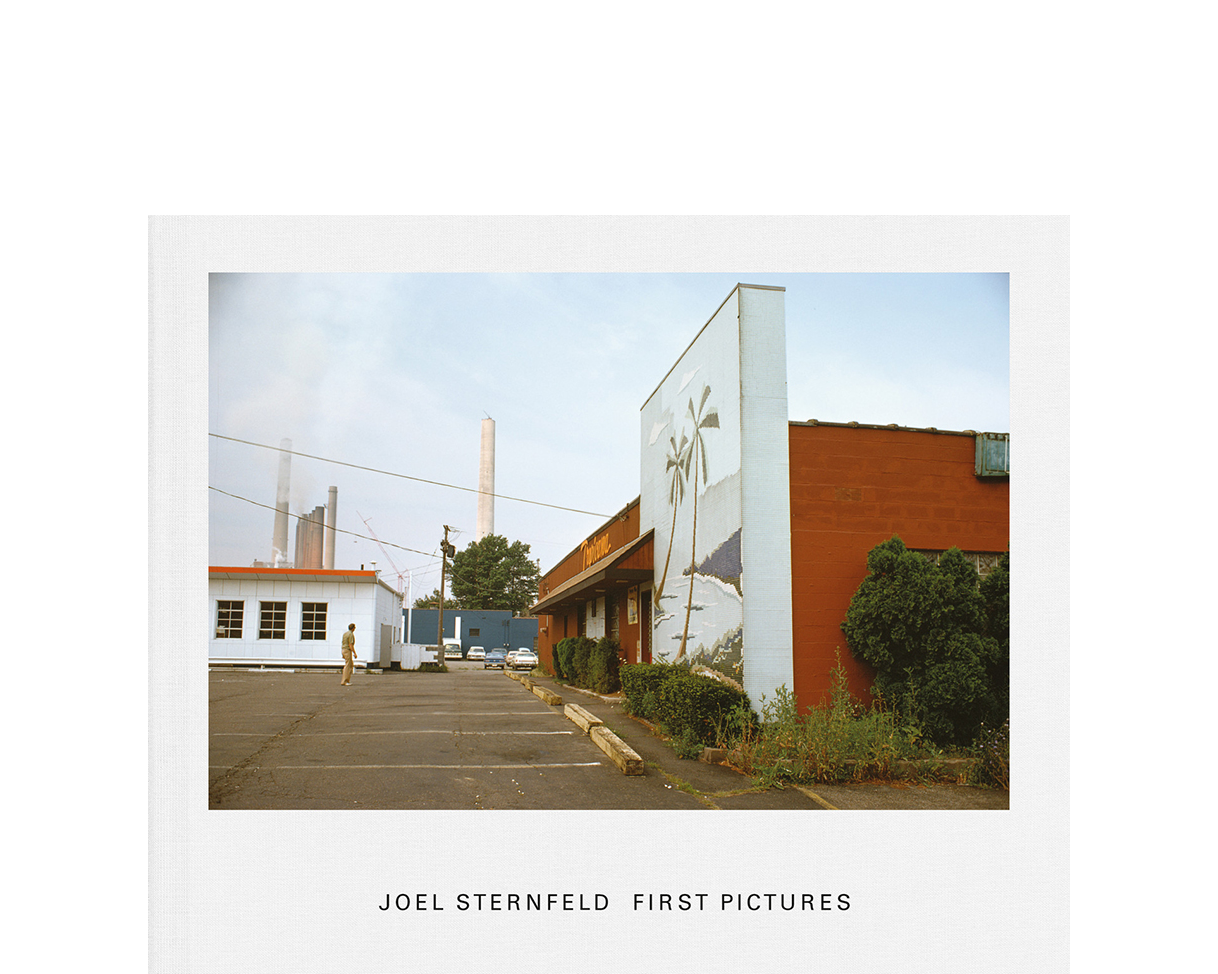

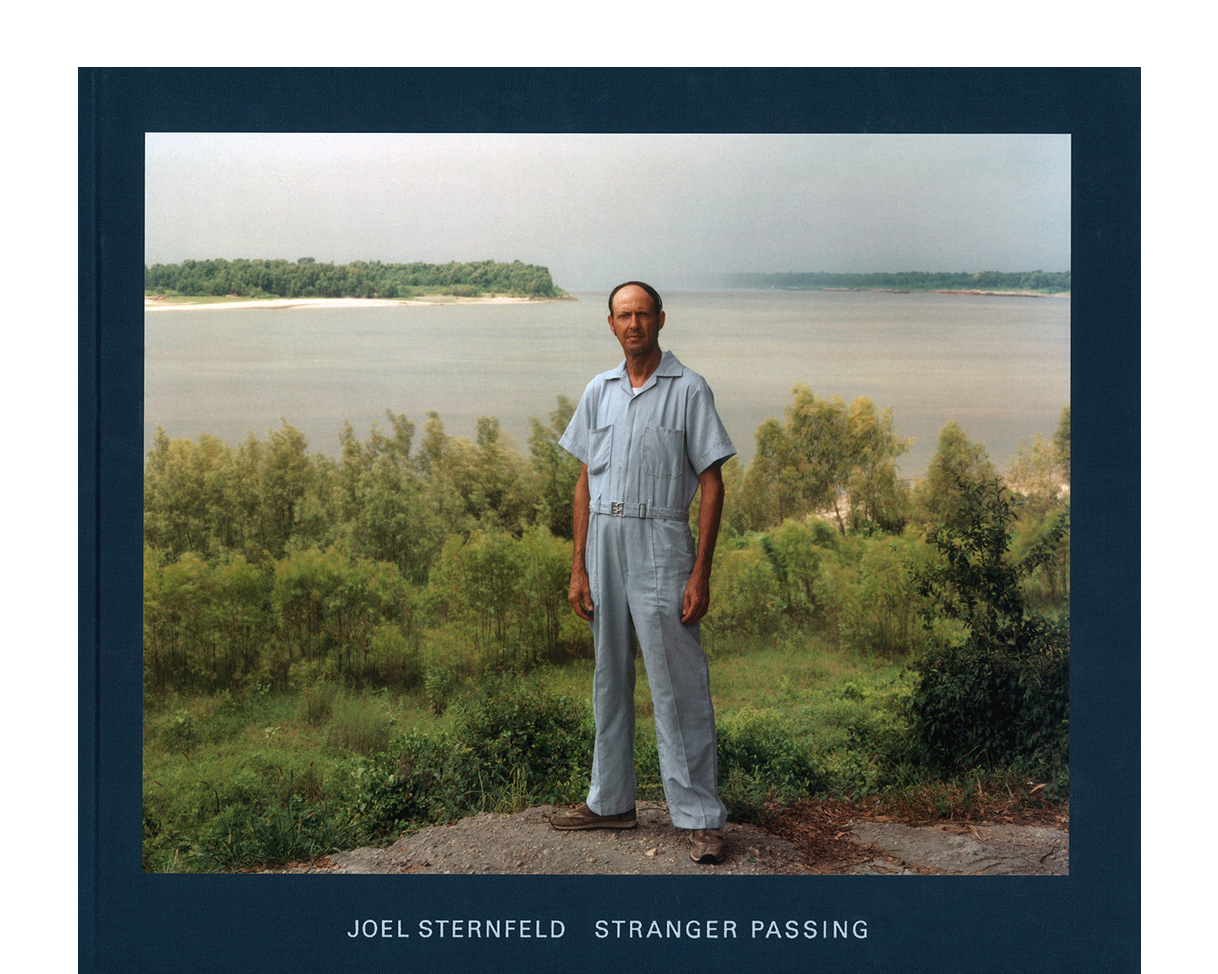

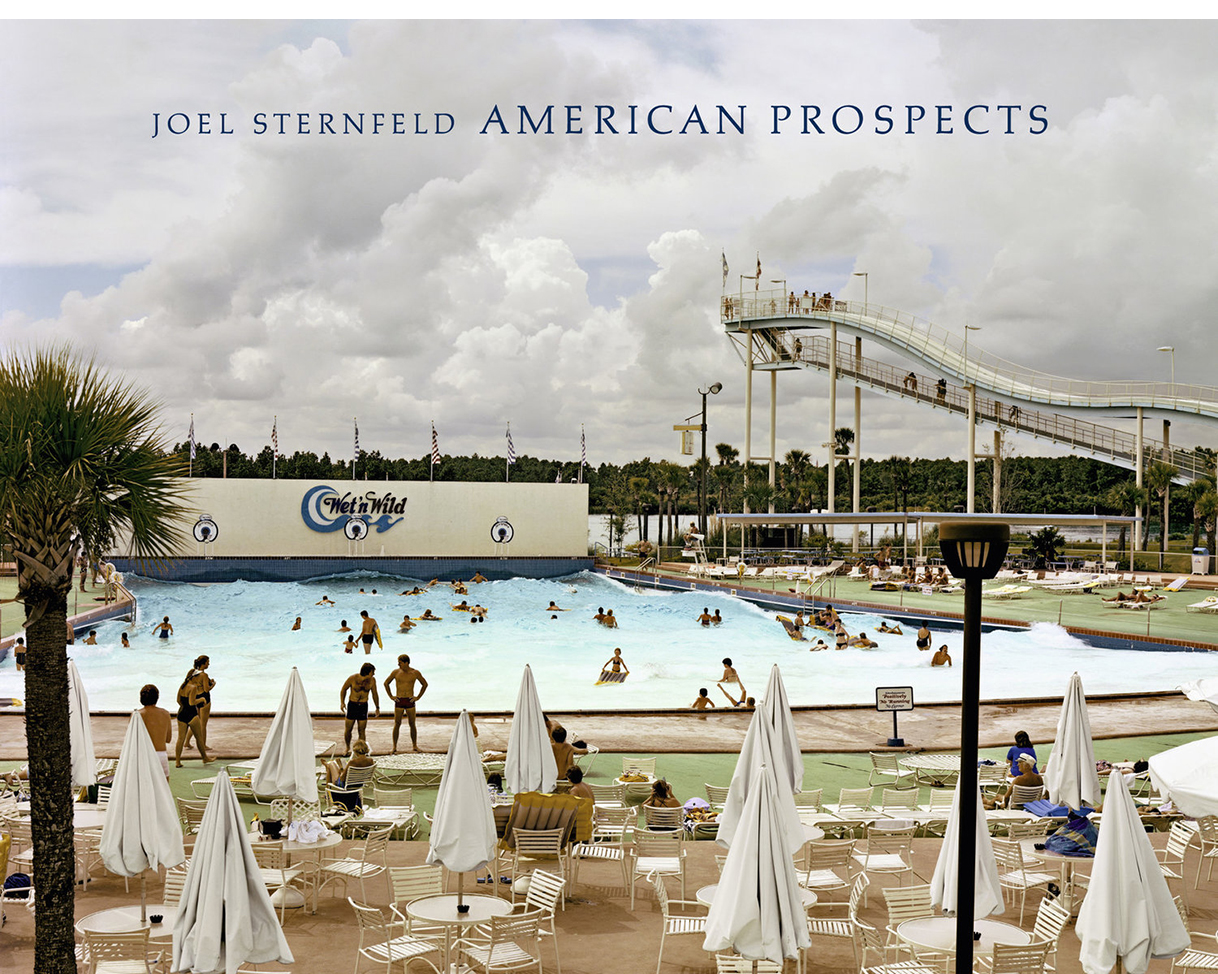

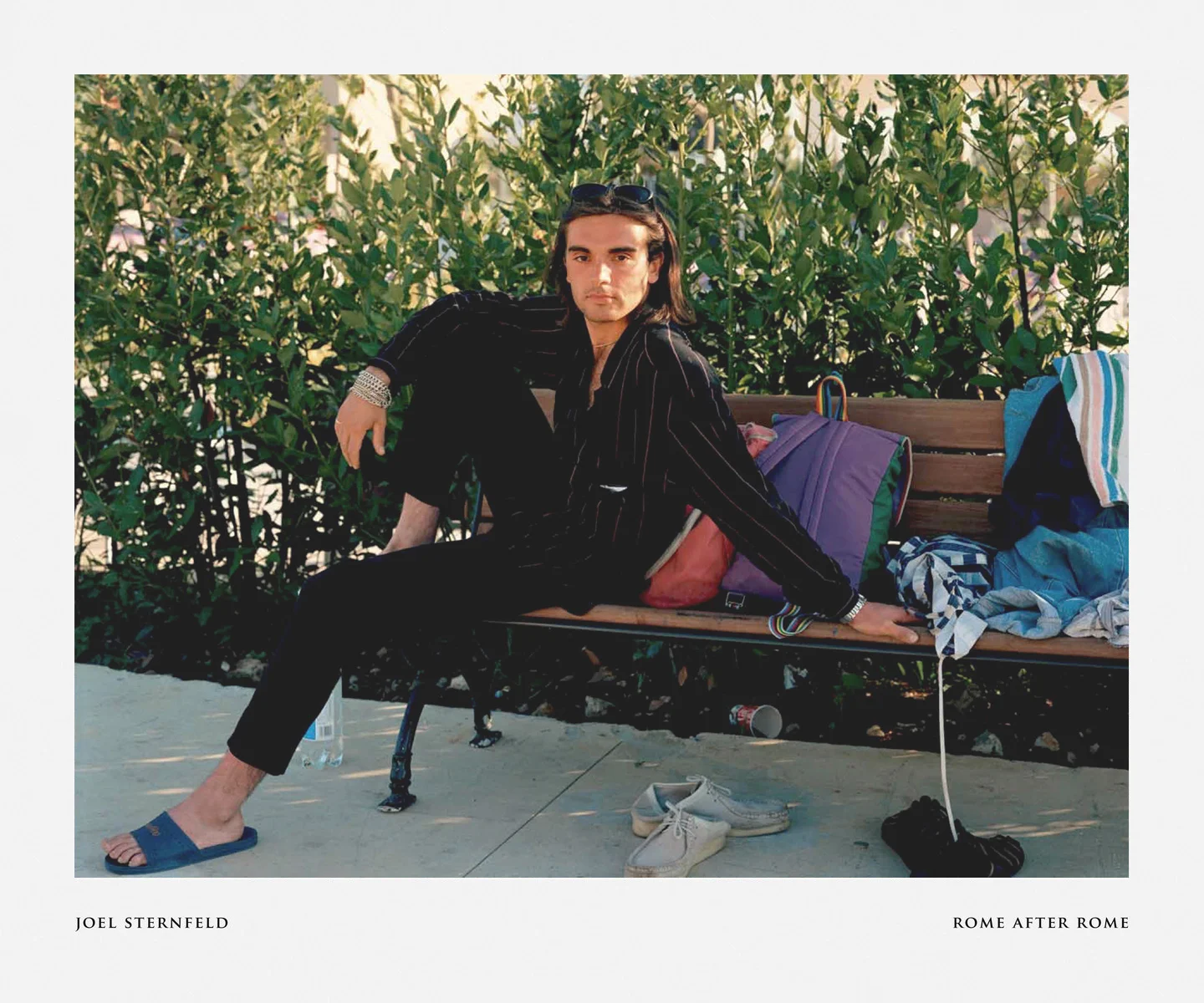

Such is the hope, anyway. In practice, as I’ve said, what you often get instead is a jumble of miscellaneous information that’s a pain to pay attention to. To find beautiful or interesting things on the surface you need a certain affinity for it, along with faith that beauty is to be found there. Affection for the surface is what I admire most about these photographs of Joel Sternfeld. His subjects exhibit a democratic ability; Sternfeld simply sees what is to be seen. You never feel that he has sought out the richest or the poorest or the most striking or the most exotic subjects. Rather, he has found ones that are enigmatic and harder to categorize, and then has accepted them just as they present themselves. The deep-browed, bearded man standing on the prairie by his car like a great patriarch we somehow never heard of was evidently happy to be seen in exactly that way by the photographer or by anyone; the lawyer carrying his laundry to the dry cleaners was perfectly available, standing at a vending machine on the corner of a New York street.

The surface in these portraits of people is weighted with the vast amount it doesn’t reveal. For starters, we don’t know any of the subjects’ names. Their histories and true personal circumstances are usually a mystery, too. Questions gather around. Why is the Santa Monica lady carrying her pet rabbit with her on a shopping trip? Who are those kids dressed up for the prom, and is the boy of the couple of a dangerous fellow, or just trying to look like one? Where did the woman in the sari at the gas pump come from, and why is she holding the gas cap as if it were a sacred object in a religion unfamiliar to her? Nowadays, cameras could follow these people home, film them round the clock, and take up all these questions and plenty more. And indeed nowadays cameras sometimes do. Much of the elegance of these portraits is that they don’t pursue the questions, that they leave them unsolved.

Observing just what’s in front of you is a discipline, like meter and rhyme in poetry. It’s also a higher form of tact, circumspection, ever forbearance; in portraits, it’s an acceptance of a person’s unlimited possibilities. Despite the information contained in how we look, we could be almost anybody. We’re grateful when someone sees us accurately without summing up too comfortably. Sternfeld is that kind of observer; he sees, but he leaves the conclusions to others - to history, maybe, or to God. Neither the best not the worst that a person can be is ruled out. On the question of the content of a particular human soul, he maintains a strong agnosticism.

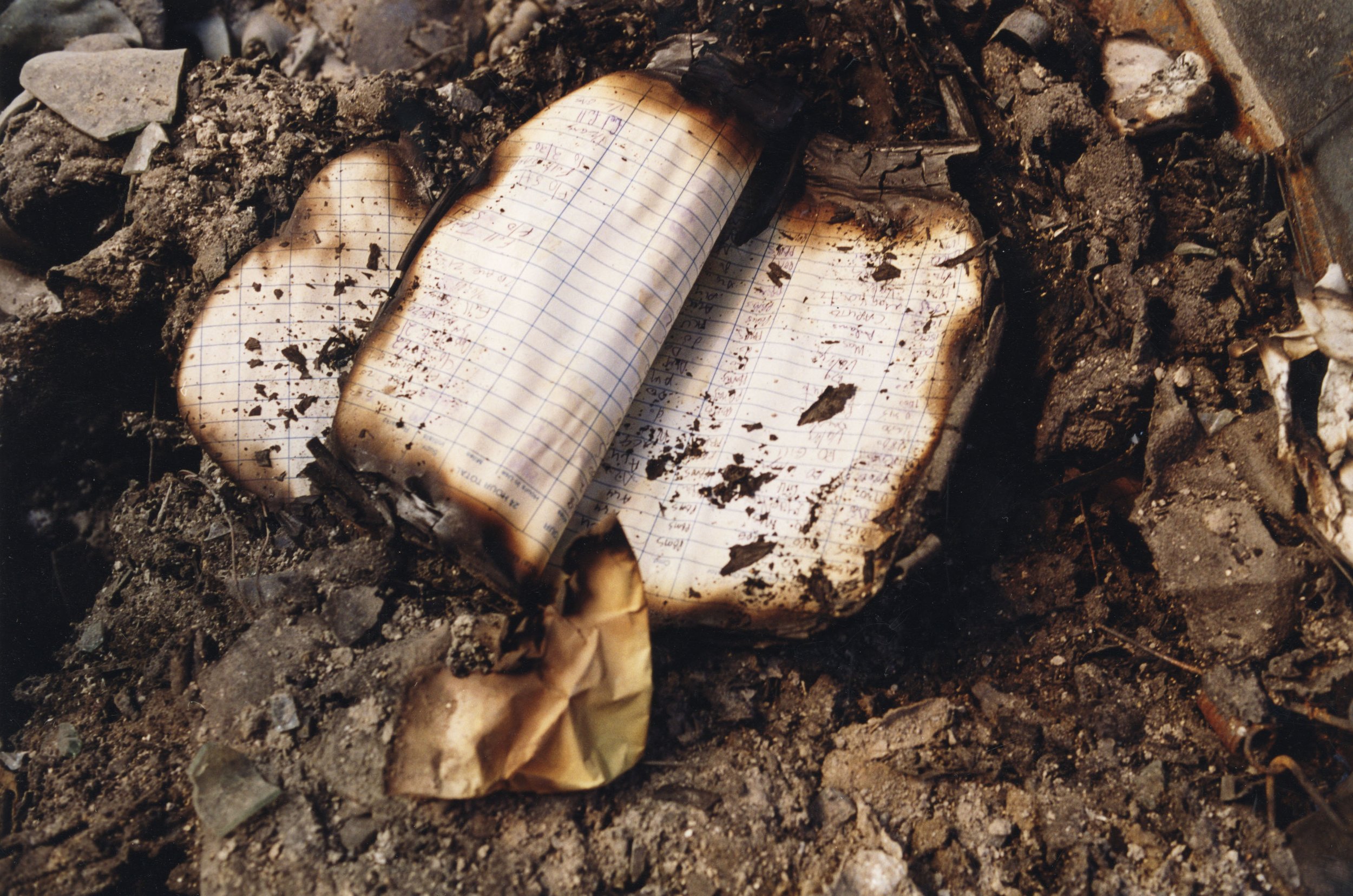

And with this uncertainty for a faith, how beautiful the pictures are! Running through all these photographs is a quiet passion for the multiplicity of America, for its commonplace loveliness generally ignored. A bare patch of bulldozed dirt next to the sidewalk of a newly built house might bot seem that lovely at first, but it you look at it again, it actually is. Often what Sternfeld’s photographs describe is endless, shaky potential. The unreadability of what he sees on the surface only enhances the county’s mystery. Endlessness of possibility makes for longing; longing is the essential American emotion which these photographs hold.

This could be such a great country. The sketch of what it could be is always out there somewhere, flickering, waiting to be filled in. I think my urge to eavesdrop is a search for clues and dispatches from the country that I know exists but so far has eluded me. More purposefully, Joel Sternfeld seeks that country here by looking at his fellow citizens and then looking again, registering what’s to be seen int he ordinary light of day, as if by the very intensity of his seeing he can summon that country into being. His photographs are a visionary act that compel us to see as he does - to look, re-look, accept what’s there. When we do, the true and amazing image of that elusive country beings to emerge.