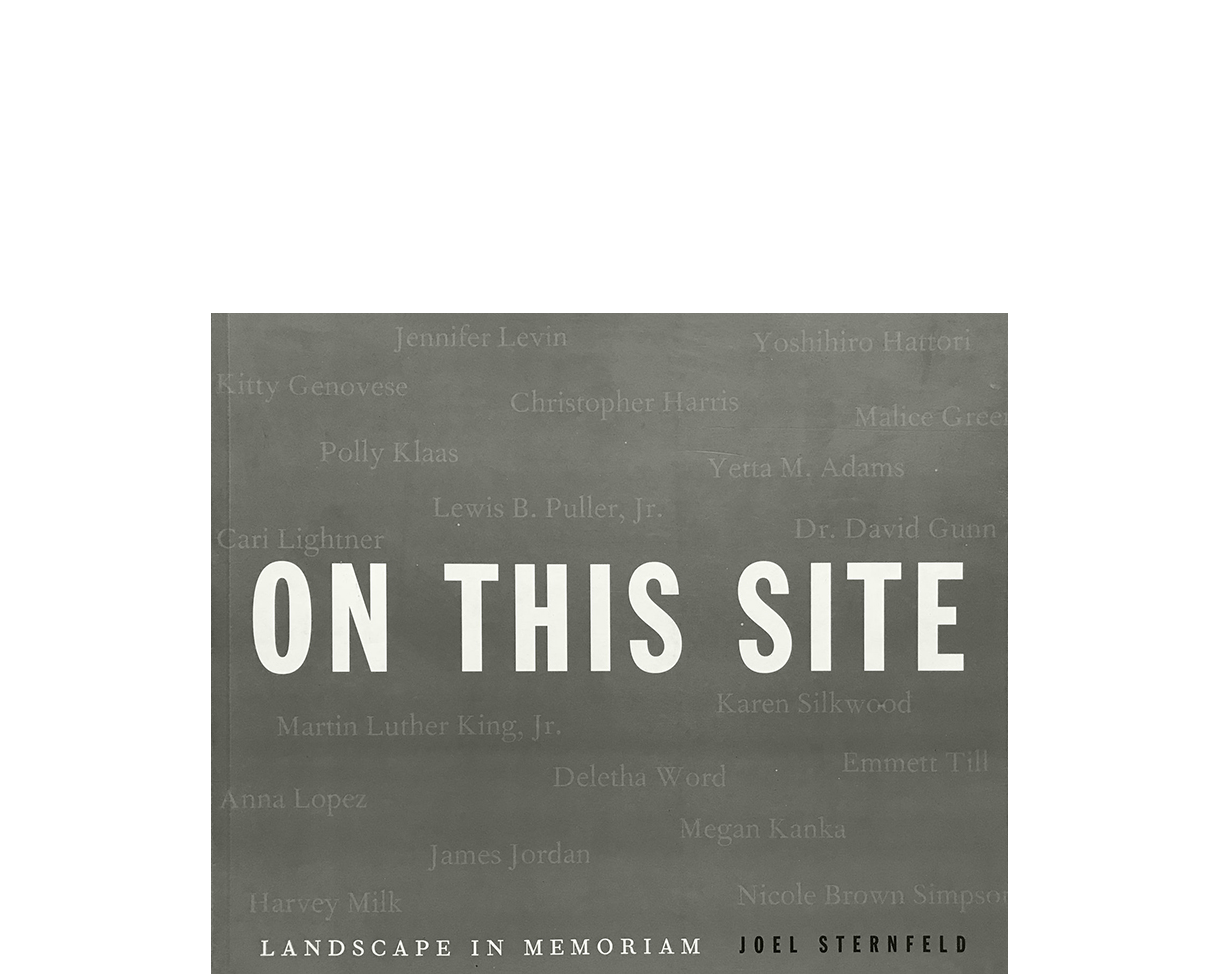

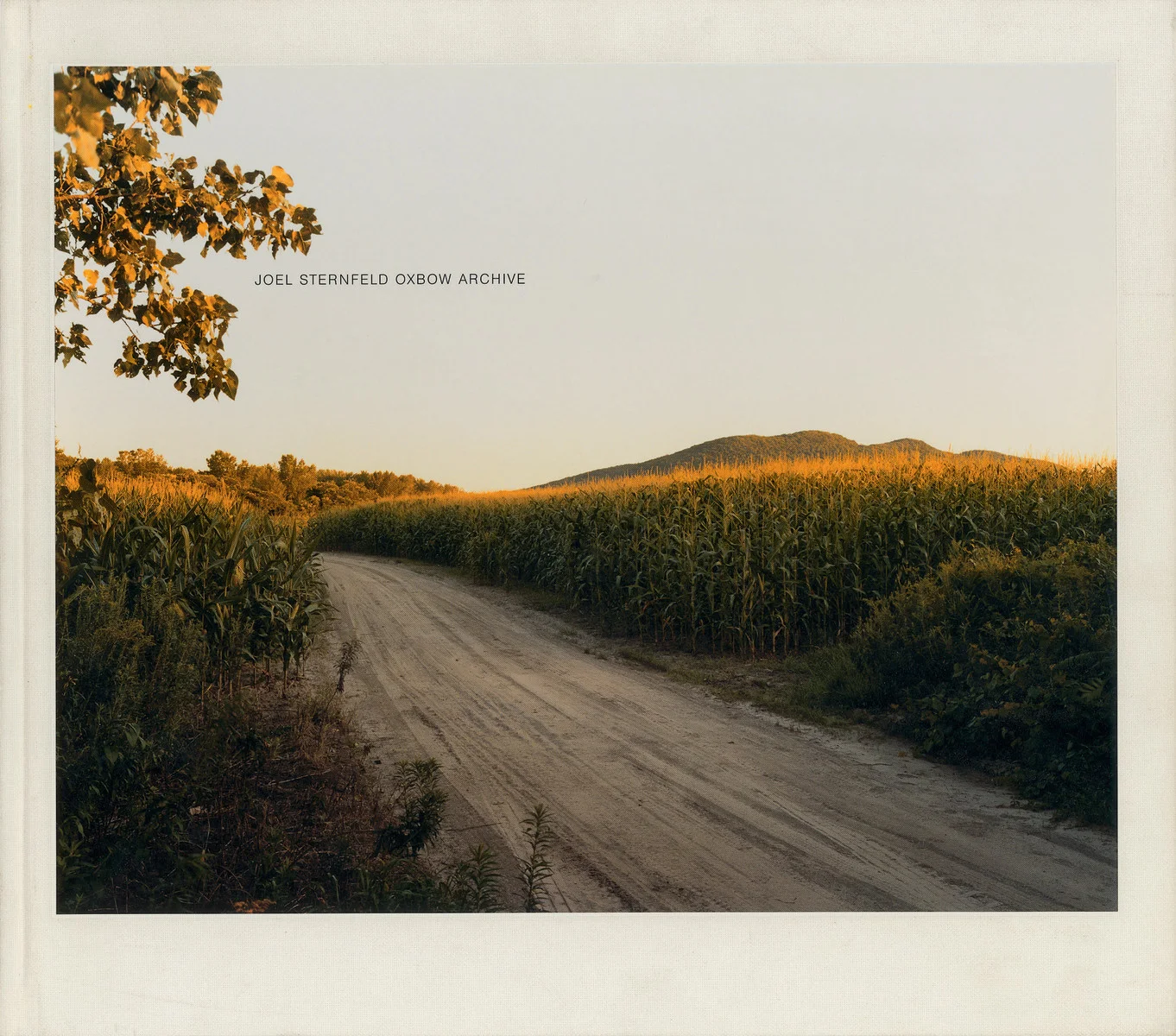

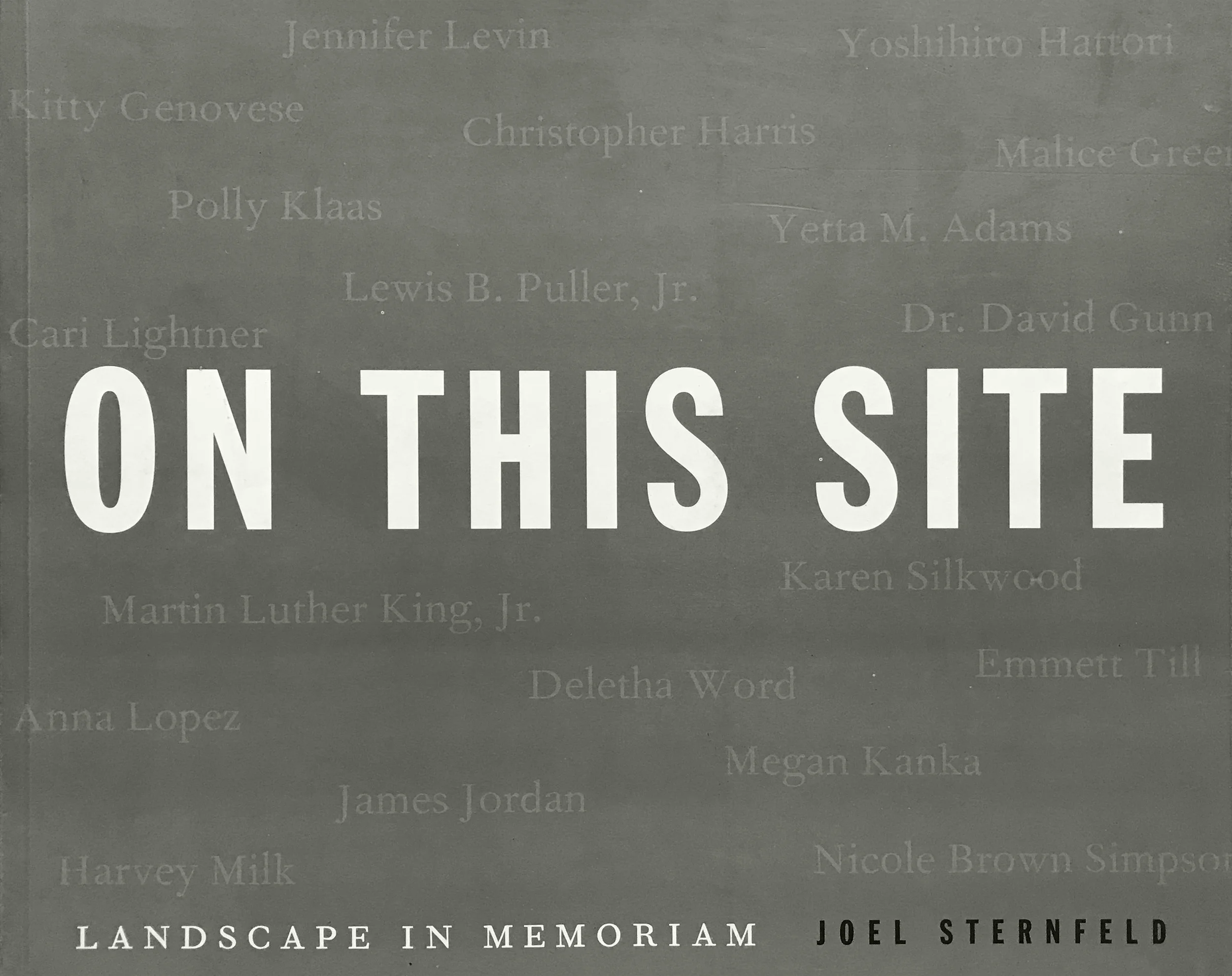

On This Site

A cemetery in Fair Oaks, California, a Sierra foothills suburb of Sacramento. Although it's a cool, gray, mid-January morning, the magpies are so active that one is forced to think of spring. I've come to visit the grave of Cari Lightner, a young girl who was run over by a drunk driver in 1980. Being here has particular meaning for me; my brother Gabriel was killed in an automobile accident. In my mind, I have associated her death with his.

As I wander, I see other graves. “Beloved and Loving, Married 74 years.” He died at 100; she at 102. One man has a picture of his Harley engraved on his tombstone. Another reads: “Cha Cha Grandma.” What does that mean? Was “Cha Cha” a family way of saying good-bye? Is what we are at the end ultimately what we are?

In front of me, a green copper marker from the 1930s reads “OUR BOY.” I remember my father crying “my boy, my boy” for my older brother Andrew who died of leukemia when he was eleven and I was ten. Across the way is a black tombstone; an etched portrait shows a young man of twenty, the inscription tells me: “Patrick bravely battled leukemia for two years.”

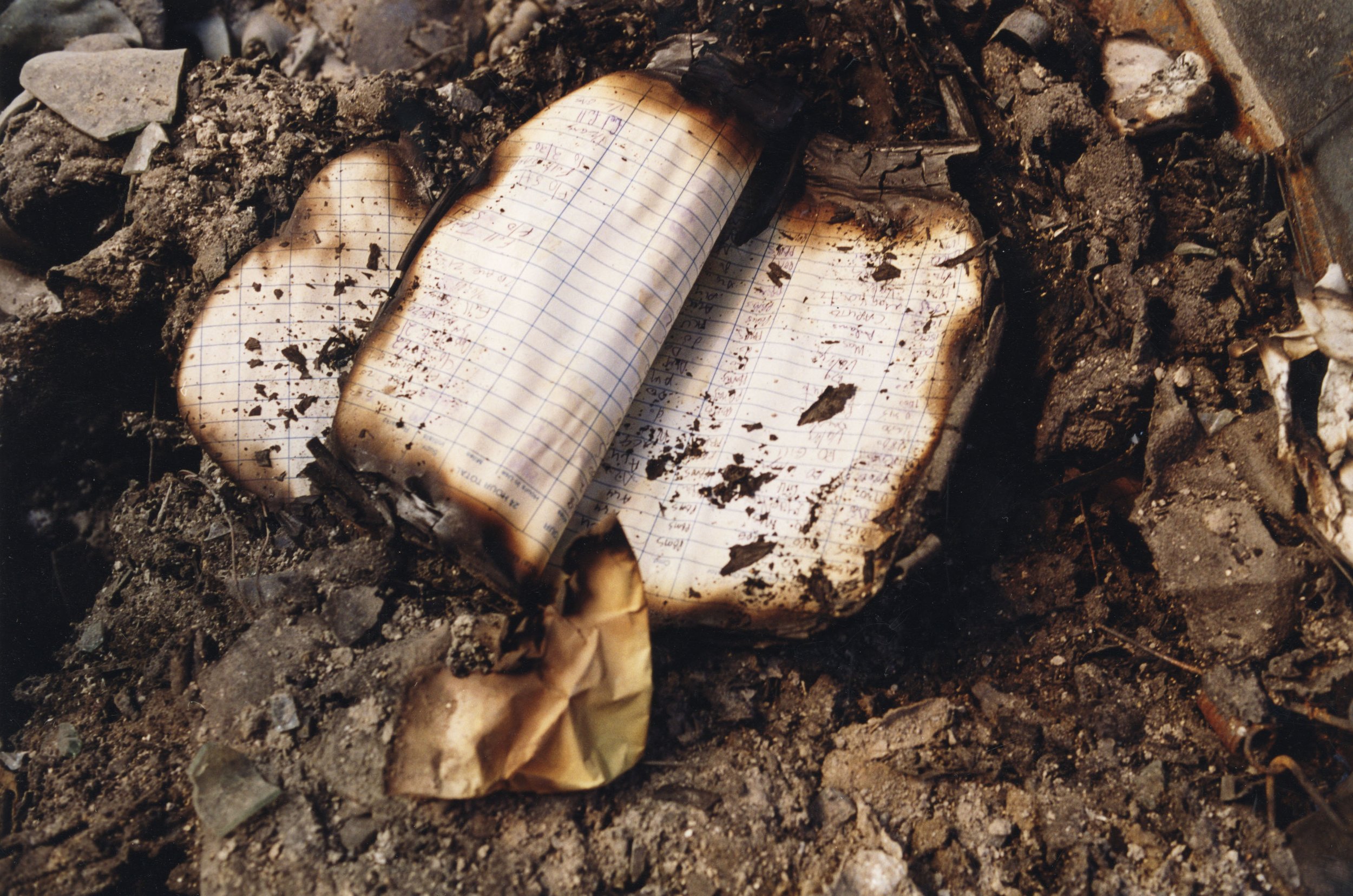

In grief, we compose these terse life summaries and elegiac messages… but for whom? What other words are so intimate and so public? Carved in stone to withstand wind and time, they speak to immortality; they console those who wish for consolation; they give pause to a stranger.

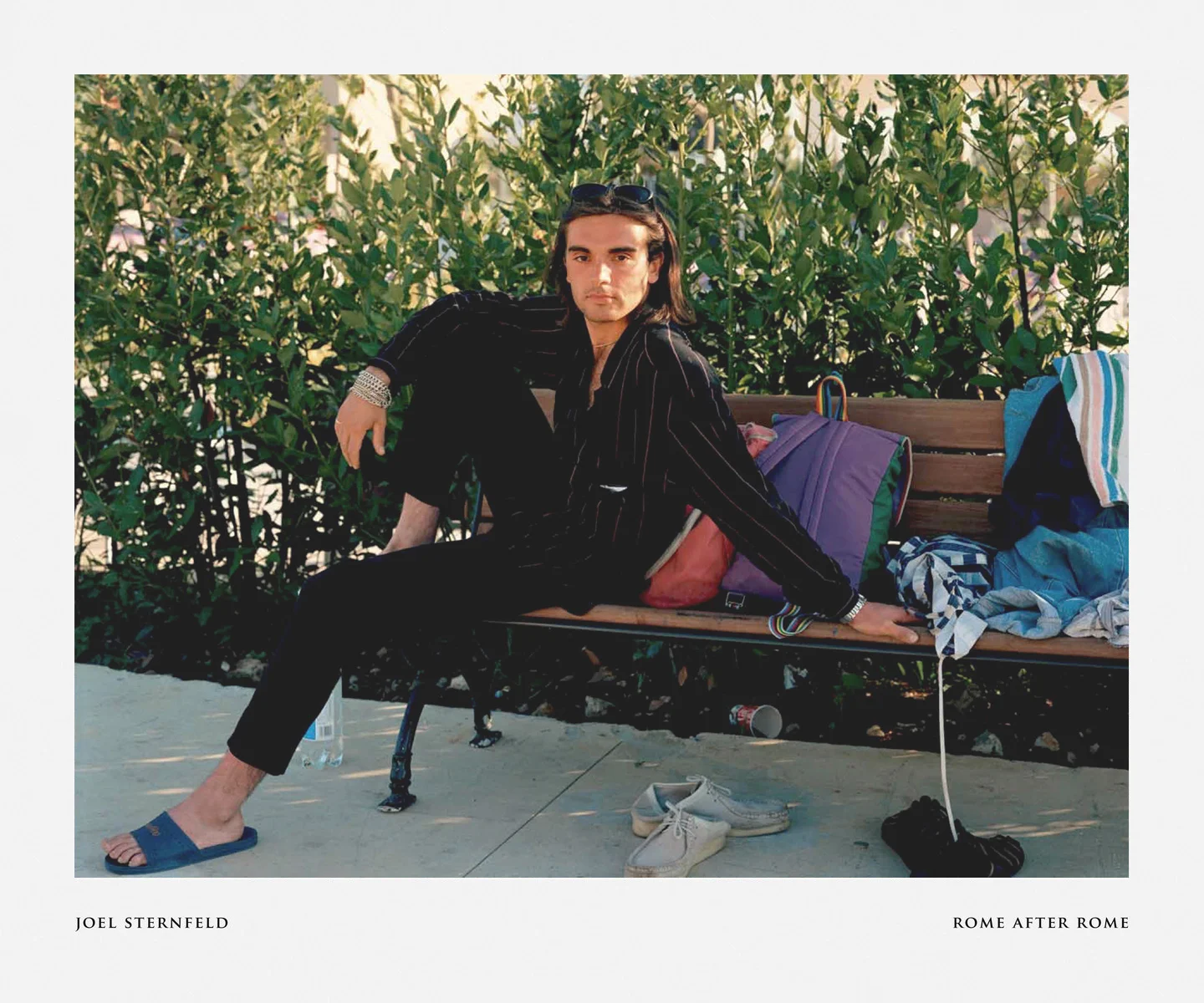

In 1990, I went to Italy and spent a year photographing the countryside around Rome. As I drove, I often saw roadside crosses and shrines at places where individuals had lost their lives in automobile accidents. Amidst the aqueducts and tombs of ancient Rome, they formed their own landscape of memorial. Each time I past one, I would slow down. I wondered if the families who build these memorials new that they would become cautionary as well as sacred.

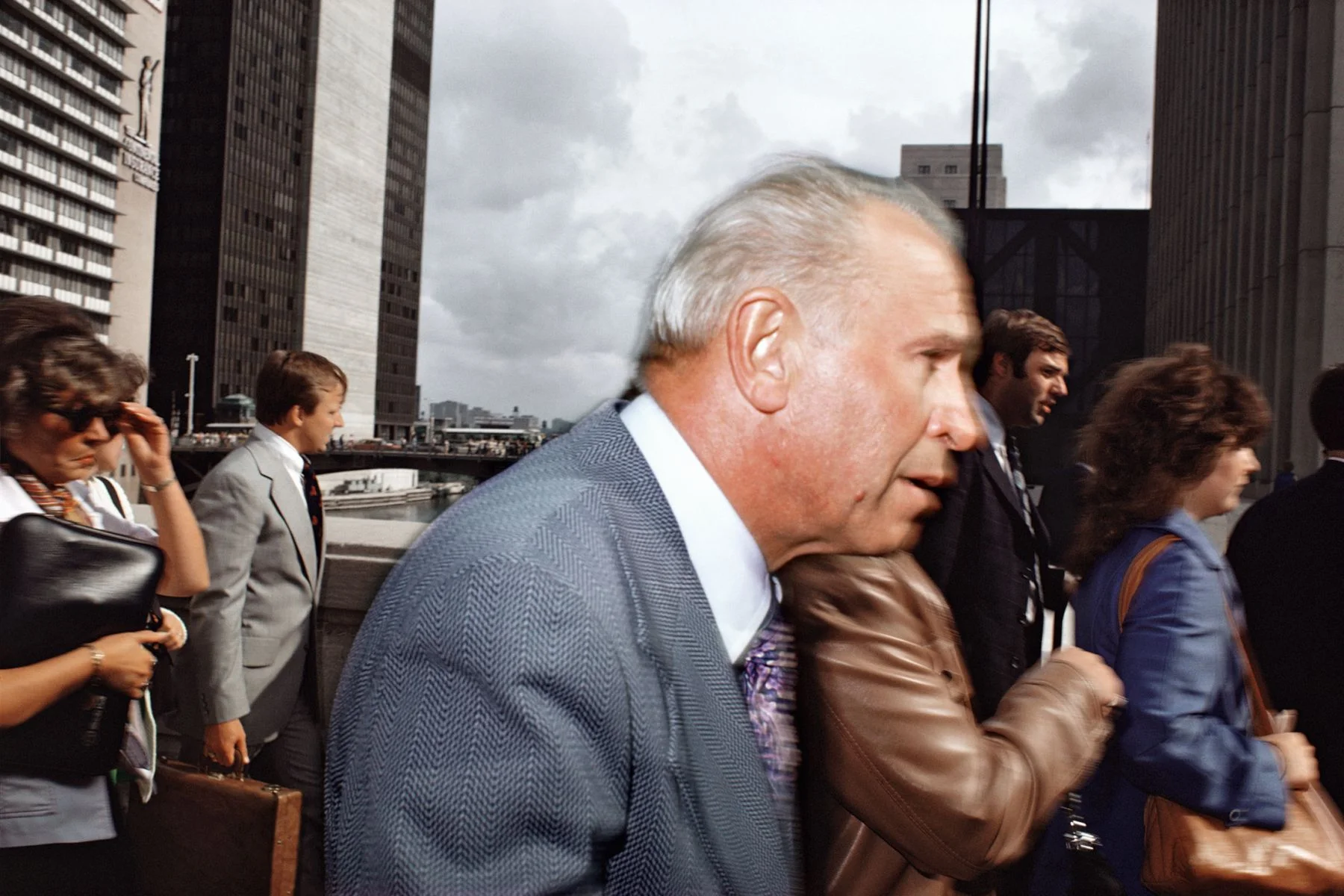

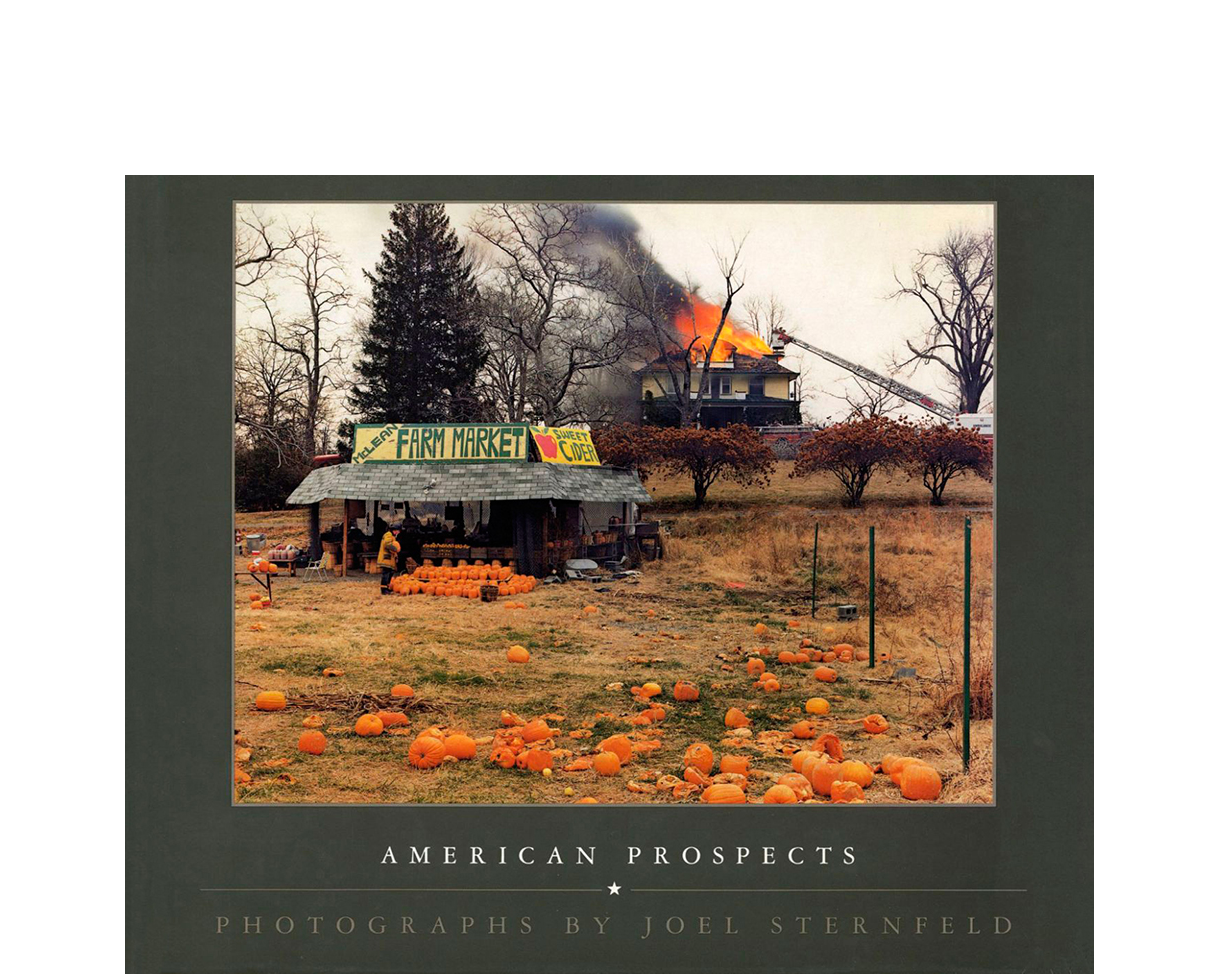

When I returned to the United States, I was struck by the accounts of violence that I read the newspaper; the vicious and the random nature of the crimes seemed more extreme than I remembered, or perhaps it was the reporting that made them seem so. I began to reconsider violence in America. When it came time to photograph again, I found it difficult to see landscape as I had seen it before.

Three years ago, on a day in late May, I went to Central Park to find the place behind the Metropolitan Museum of Art where Jennifer Levin had been killed. It was bewildering to find a scene so beautiful… to see the same sunlight pour down indifferently on the earth.

As I showed the photograph of this site to friends, I realized that I was not alone in thinking of her when walking by the Met. It occurred to me that I held something within: a list of places that I cannot forget because of the tragedies that identify them, and I began to wonder if each of us has such a list. I set out to photograph sites that were marked during my lifetime.

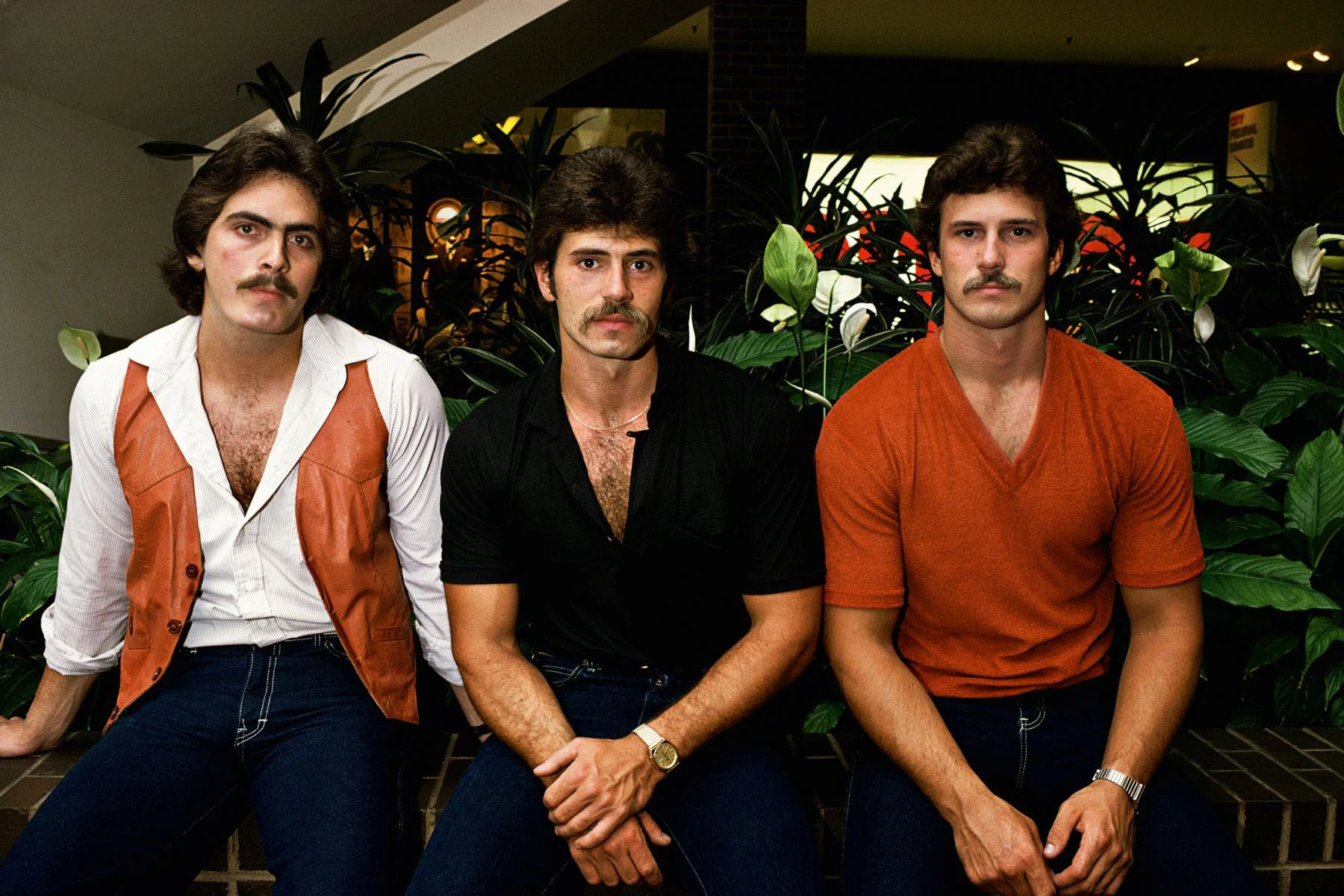

Yet, there was something else that drew me to this work. I think of it as the question of knowability. Experience has taught me again and again that you can never know what lies beneath a surface or behind a facade. Our sense of place, our understanding of photographs of the landscape is inevitably limited and fraught with misreading.

Two and a half years later, what has the experience of making these photographs taught me? When I first began, I thought I had to find all the answers; I had to know if America is more violent than it was in the past, if it is more violent than other nations. I realize now that these questions are not the crucial ones. Each tragedy demands its own remembrance. Each of them is ours.