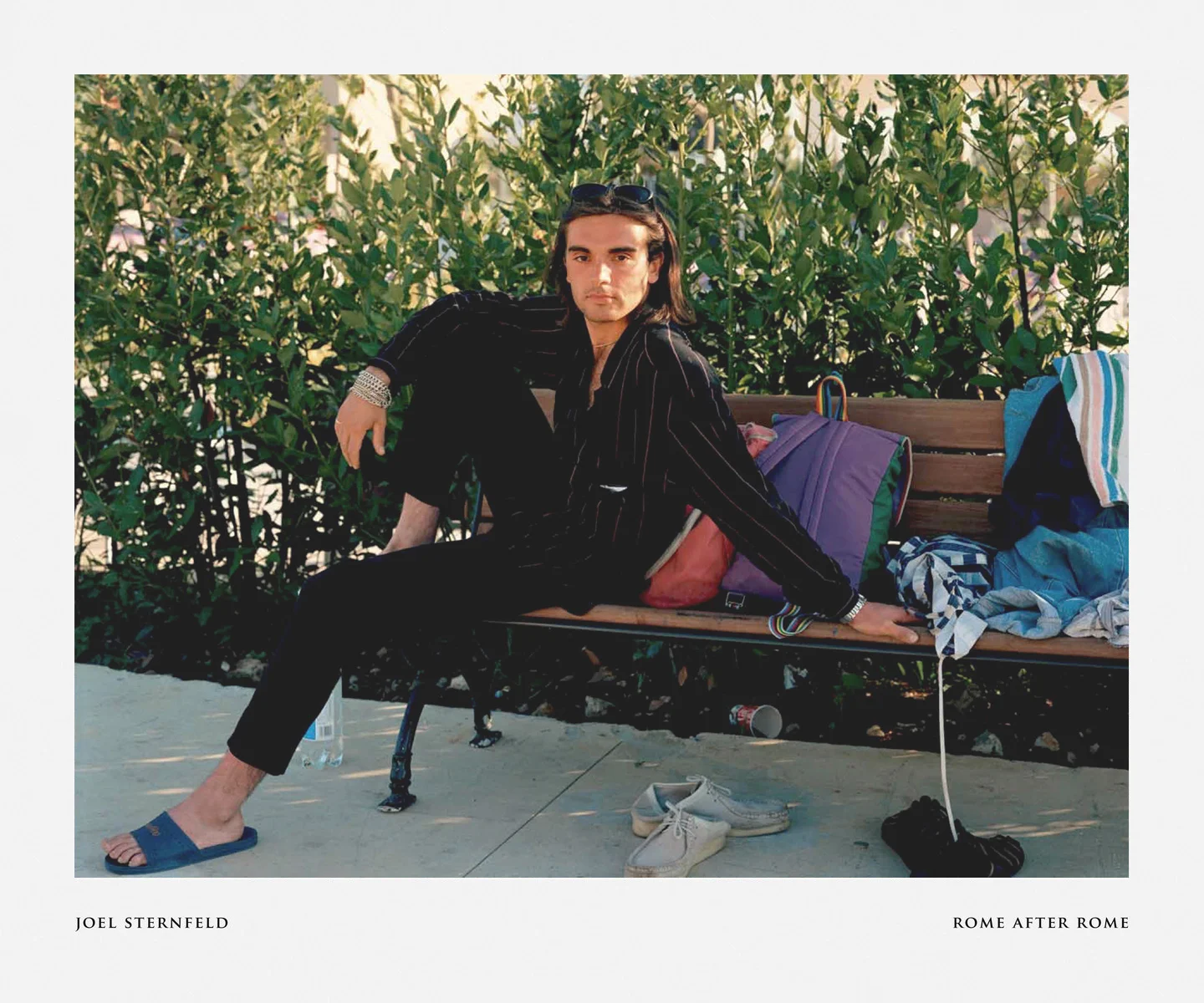

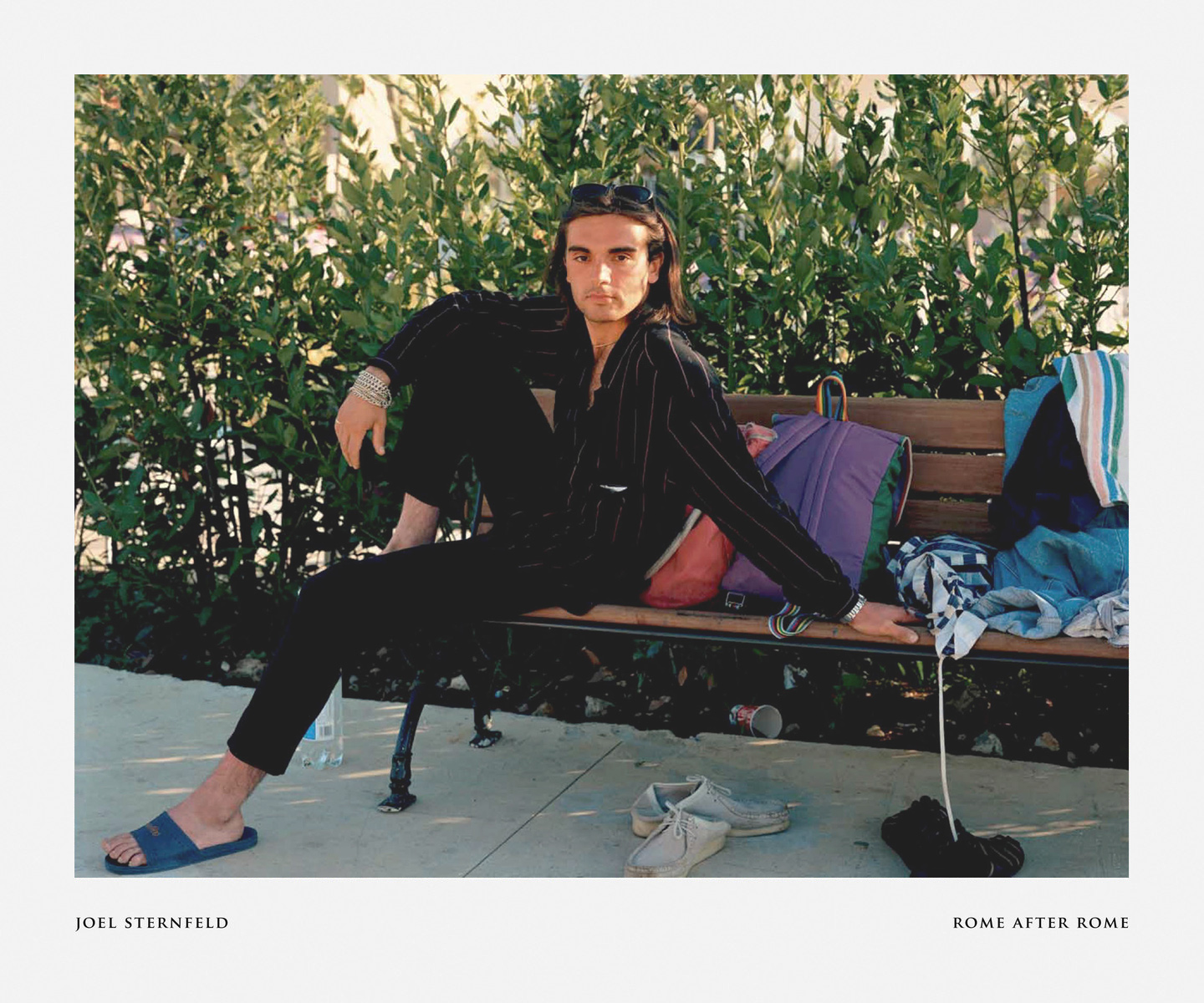

Rome After Rome

Walking across deep plowed fields of the Roman countryside, on a day in August, I am like a small ship facing directly into oncoming waves: there is a difference in height of at least a meter between the trough and the crest of the furrow. Clumps of hard brown earth make the going choppy. And it is hot—it is slightly before noon but in an hour no one, but no one, will be seen outside.

I am sailing a straight course for Cinecitta Due, the glass and chrome shop- ping mall with air conditioning and, more importantly for my purposes, Due Palme Gelateria where a triple portion of some of the best gelato in Rome awaits.

As I cross the waves I might spy a bit of Roman pottery or a Roman coin (the Via Tuscolana went right through this field) but I am not thinking about antiquity; I am trying to decide today’s flavors. And why not? The Emperor Nero, we are told, had blocks of ice brought to Rome from nearby mountains (by runners no less) which were then shaved and used to make a kind of fruit sorbet. Regardless of its truth the tale makes sense on a day this hot.

Going to the mall after spending the morning in solitary communion with the ruins of the Claudian Aqueduct (and the Anio Novus Aqueduct piggy- backed on top of it) amidst tall, yellow grass and green umbrella pines is not necessarily inconsistent: I got here by subway, the Giulio Agricola stop on the A line. And I am walking in the field where Fellini filmed a statue of Christ being airlifted by helicopter over the Claudian Aqueduct for the open- ing sequence of La Dolce Vita. Aside from a reference to the Second Coming (to decadent post-war Rome), did Fellini simply want to remind us that in Italy the past is always very much present?

To describe the geographic parameters of the Campagna is difficult. By one definition it is the rolling plain south and east of Rome, bounded by the Mediterranean Sea and the nearby Sabine mountains and hills to the north. Others consider it to be the Agro Romano, or any place outside the city center where crops can grow—and sheep may graze.

Further complicating a definition, at times over the past two millennia the Campagna has crept, like fingers, into Rome itself. Earthquakes, fires (after the fall of Rome marble buildings were intentionally burned to extract lye) and building collapse left empty lots that could be used for gardens or goats. In fact, the Roman Forum was a grazing ground until King Victor Emmanuel ordered it cleared of rubble in 1870 and Mussolini completed the task in the 1920s.

Describing the Campagna only leads to confusion because its character as a place has transformed so many times over the centuries. In pre-Roman days it was by legend a shepherd’s paradise, but by the time of the actual founding of Rome, it had become swampy and thus malarial. After Rome drained the swamps, agricultural villages and great estates came to dot the empty plains of the Campagna. The most majestic of these was Hadrian’s sumptuous villa out- side of Tivoli from which he at times ruled the Roman Empire, but there were numerous others. 500 meters to my right are the ruins of the Villa dei Sette Bassi, ‘the seven-story house’. A homeless man is living there now. The other day as I wandered through the ruins I frightened him and he frightened me.

With the final fall of Rome the Campagna became inhospitable again, a place for brigands and misfits, a dangerous area one hurried through with carriage windows closed as the very air of the Campagna was reputed to be insalutary. In Moby Dick, Melville refers to “Rome’s accursed Campagna”.

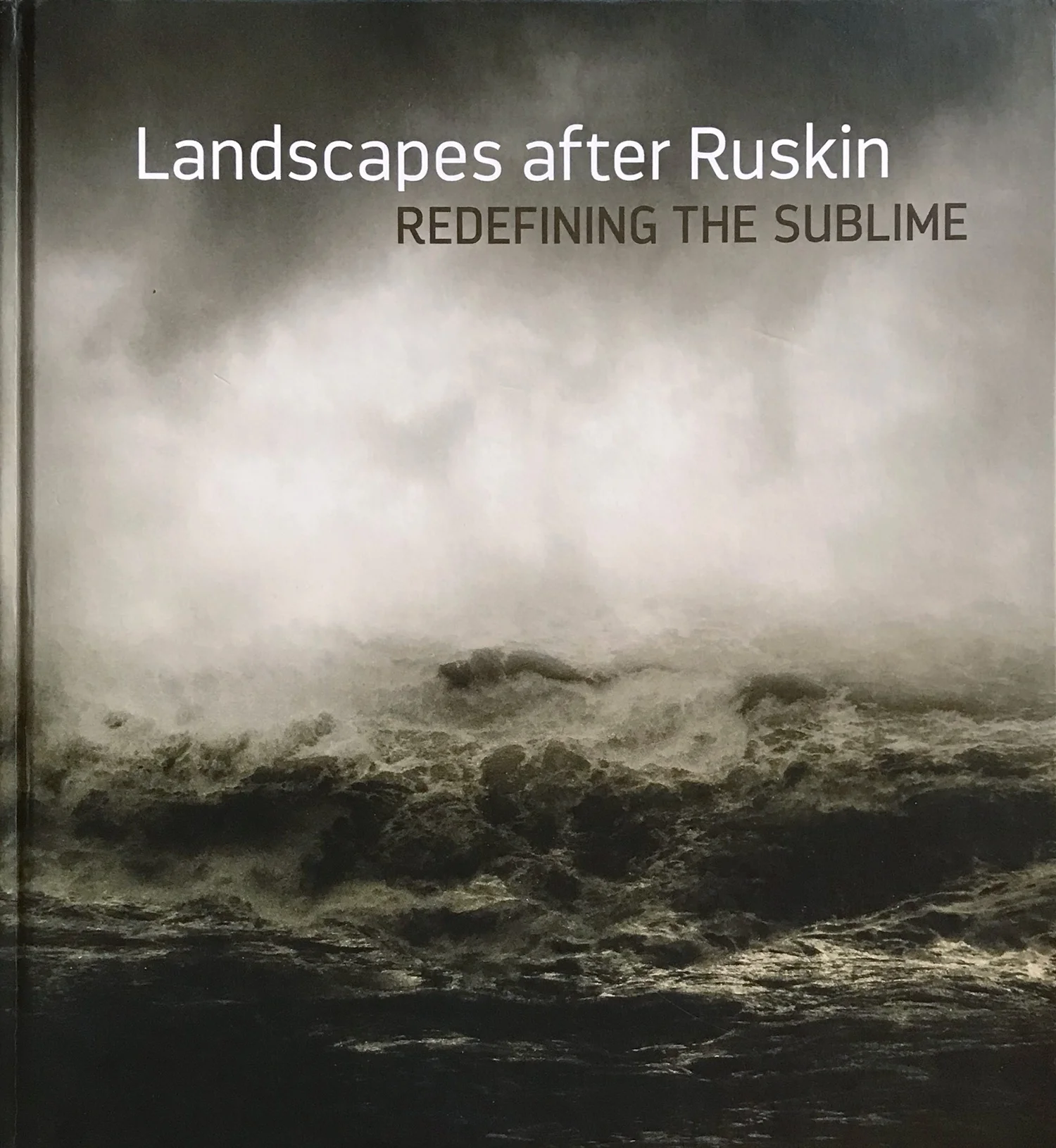

Accursed it stays until the early 1500s when painters begin to arrive (along with scholars and tourists). Over the next 300 years they turn this unlikely candidate into the most painted landscape in the entire Western canon. The curator and Corot scholar Peter Galassi writes that it has come to occupy “a special status not shared by any other landscape”.

What brings these Northern European, and later American, painters to Rome and to the deserted Campagna? The answers are many: the Vatican was there, the Renaissance had begun in nearby Florence in the 14th century — there were actual Raphaels to be seen in Rome. (Curious that the Renaissance comes upon the heals of the Black Plague, also curious that the painterly rush to Rome follows on the heels of the sack of Rome in 1527.)

And the light! The beautiful light of Rome which has been likened to the light of the Artic (how lovely to think of the Artic on this burning morning). I have come to believe that it is at the latitude of Rome that the soft light and warm, moist air of the South of Italy and of Northern Africa meet the crisp air of Northern Italy and Europe, and that it is this mixture that makes the light so unlike any other.

Dutch artists, most notably Albrecht Durer come in the 15th century but it is with the arrival of Claude Lorrain and Nicolas Poussin from France that the stampede to devour Rome and all of antiquity begins. Lorrain never leaves. He creates paintings that combine history and myth, realistic depiction and idealized fantasy. In Lorrain’s work the accursed Campagna becomes an Ar- cadia where gods cavort and the world is floating in an Italianate haze that is the pure residue of ancient Rome — and Greece. Curious that a marshland might come to be the principal signifier of edenic life for the Western world. Rome once ruled much of the known world but ever since it fell Rome has belonged to the world, its image and meaning determined by outsiders, stranieri.

Many others followed, herds of painters on regularized circuits painting pre- scribed views (vedute). They were led by Corot, Turner, and the Americans who would come to be known as the Hudson River School painters, foremost of them Thomas Cole. Rome held a particular fascination for the Americans who envisioned their young republic with its lofty ideals as the true incarnate of Roman ideas of democracy and citizenship.

But what led them to the Campagna? Why not concentrate as Piranesi and others did on the city that deemed itself eternal? I believe there are several important pragmatic and aesthetic reasons.

In order to travel to Rome painters would have likely passed through the Campagna. Like Transylvania, which has suffered a bad reputation ever since the publication of Bram Stoker’s novel Dracula, but which is, in fact, quite beautiful and not at all vampirish, the disreputable Campagna has its own, albeit different, sublimity. Painters and others traveling through it must have seen this but it may have served them to perpetuate its stygian reputation as a means of aggrandizing the rigors endured to achieve Rome. When it finally lay before him, a latecomer, Henry James, wrote of the “great violet Campagna stretching its idle breath to the horizon ... a wilderness of sunny decay and vacancy.”

Passing through the Campagna pilgrims might have had their first view of the dome of the Vatican several kilometers in the distance (in pollution free days). It was a sight that sometimes induced fainting—and perhaps a desire to go back to the Campagna after settling into one’s quarters in Rome, to recreate that literally breathtaking view on canvas.

A simpler reason for going back out into the countryside: painters (or photo- graphers) like, to the point of obsession, a wide view, a horizon, and of course a sky — and the ability to stand and work in “the best spot”. Difficult to do in a city with laundry hanging everywhere — and poor sanitation.

Remember also that the Roman Forum and many other important sites were yet buried beneath rubble when the painters arrived. In the Campagna the very opposite prevailed. Large and dramatic ruins sat in isolation — in a land- scape that seemed to encourage the mind to roam in time. They could be painted at any time of day from from any point of view with only the light dictating the choice.

Monuments in the Campagna endured because they were functional objects to begin with and thus built to last (which is not to say that aesthetics were ig- nored: sometimes an aqueduct was built in ancient Rome in the style of one built 200 years previously because the earlier one was considered charming).

There were eleven aqueducts built to serve Rome. So proud was the city of its water supply that each of the twelve or thirteen hundred public fountains spread throughout the city had a spigot (referred to for its shape as a naso or nose) continuously running. This was the stuff of conversation and legend in the ancient world.

Aqueducts were largely underground pipes in the mountains but when they marched across the final kilometers to Rome they came above ground and maintained the perfect incline to keep the water moving downhill. The trick was to keep the water in motion, but not so fast that rocks and stones which inevitably fell into the water channel would tear it apart, and also so that the water did not burst the pipes when it finally arrived in the city. Approx- imately three meters of descent for every 1,000 meters of length was the slope that did the trick, but how the Roman engineers achieved this without computer-aided design is wondrous.

Neither time nor the elements could destroy the aqueducts and so when one encounters an aqueduct with missing arches it is fair assumption that they were repurposed into medieval towers or grand homes or other building projects.

So too, the great tombs that line the Appian Way were built to last to keep grave robbers out, and to prove monumental love. They were located just outside the Aurelian Walls thanks to a Roman interdiction of burials within the walls. Sometimes reaching a height of 21 meters, as in the case of the tomb of Caecillia Metella who was, according to Lord Byron, the “wealthiest Roman’s wife” or a daughter according to others. During the Middle Ages a family bought the tomb and fortified it. They then proceeded to collect exorbitant tolls from travelers on the Appian Way, and thus were the two certainties, death and taxes, truly linked. When it was abandoned in 1485 it resisted repurposing — until it became a tourist attraction.

It was into this landscape of giant sculptural shapes on an endless plinth with a sky that offered its own chromatic abstraction that the painters wandered facilitated by absentee landlordism, and unfettered by anything but their own aesthetic dowsers. Who wouldn’t be seduced by its “silence made visible to the eye” in the words of William Cullen Bryant.

Which is not to say that the Campagna was completely uninhabited. Shep- herds and peasants lived here. One of the great students of the Campagna in the 20th century, Thomas Ashby, felt that it was “inhabited by people who were living vestiges of classical civilization”.

Ashby, whose book has been my companion in the Campagna, was director of the British School. He made it his life’s work to record every meter of ev- ery aqueduct culminating in his totalizing The Aqueducts of Ancient Rome (after its publication he committed suicide).

I often wonder if the people I meet are indeed directly descended from the ancients — or what their consciousness of a glorious past might be. There were so many conquests of Rome but here in the countryside people might have been able to hide in the tufa caves or elsewhere when conquerers came through.

Ashby, in the words of Richard Wrigley, felt an “undimmed sense of eupho- ria and veneration whenever he entered this mysterious and inexhaustible space.” This well describes my sense and that, I think, of anyone who has spent time in Rome’s coextensive environs. Goethe wrote: “In Rome I have found myself. For the first time I am in harmony with myself, happy and reasonable.”

Feeling that same exaltation I have had to ask myself what might be its sourc- es. In her magisterial and mysterious Pleasure of Ruins Rose MacCauley exam- ined the various ways that ruins might induce a sense of transformation.

I believe that one of their most central pleasures is the profound personal release that comes from standing in front of a ruin and being forcefully re-

minded of the passage of time itself—and concomitantly reminded that there will come a day when the pains and disappointments of life will surely pass. There are two brick reinforcing arches of the Claudian Aqueduct that sit in isolation from the others. From the very first time I saw them I thought of my two brothers who had each died at an early age and it gave me solace to do so.

In 1870 Italy became a nation, Rome its capital. The city began to expand into the countryside. The marshes were drained once more. The painters stopped coming.

Today to walk to the Claudian Aqueduct one must pass through block upon block of Sebaldian apartments. The ruins are still there, children still use them as play structures, climbing on them and jumping from them. But that pure linkage to a classical past is not possible. Modernity is around every bend.

In time to be will our civilization become the stuff of a pleasure of ruins? Who will have that pleasure? Will the painters come?